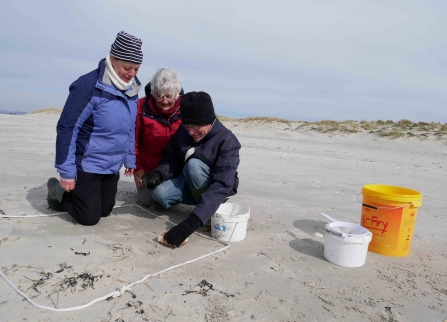

If you caught our recent blog on our use of citizen science you'll know how vital it is to our work, but we're not the only organisation to achieve bigger and better things thanks to this method. This time, we take a look at the fantastic Big Microplastic Survey to see how citizen scientists are helping to tackle one of the biggest environmental challenges of our times: marine microplastics.

Defined as plastic fragments smaller than 5mm in length, microplastics can be created intentionally – think microbeads in beauty products - or form by accident when larger pieces of plastic break down. They have been detected worldwide in soil, rivers, air, and even the depths of the Mariana Trench. The health impacts on human and animal life are not yet fully known, but there is evidence to show that they can stop smaller animals from feeding properly and carry chemicals that are toxic for certain species.